Stormwater Awareness (Why its Important to our Creeks)

by Byron Madigan, ACWA Board Member

You’re probably familiar with the term, but what exactly is stormwater? Stormwater is any type of precipitation that falls on your house, your school, your yard, roadways, parking lots, etc., and then washes into the nearest stream, river, and/or any other water body either via overland flow or through a storm drain network. Along its path, it picks up pollutants, trash and toxins that have accumulated on roadways and other surfaces and carries them straight into our waterways, potentially contaminating the water sources we use to swim, fish, and drink, and eventually the Chesapeake Bay.

Where do pollutants come from? Pollutants can originate from a variety of sources, such as fertilizers from lawns, golf courses and agricultural operations, commercial and industrial areas, faulty septic systems, livestock waste, vehicle grease and oil, and other untraceable sources, referred to as “Non-point Source Pollution.”

Unlike the sanitary sewer from our homes and businesses, water flowing into the storm drains is not treated. In many cases, storm drains connect directly to our local streams, creeks and rivers, and these pollutants, along with trash, and pet waste, can degrade water quality in our local water bodies, potentially restricting recreational activities such as swimming and fishing, threatening wildlife and human health.

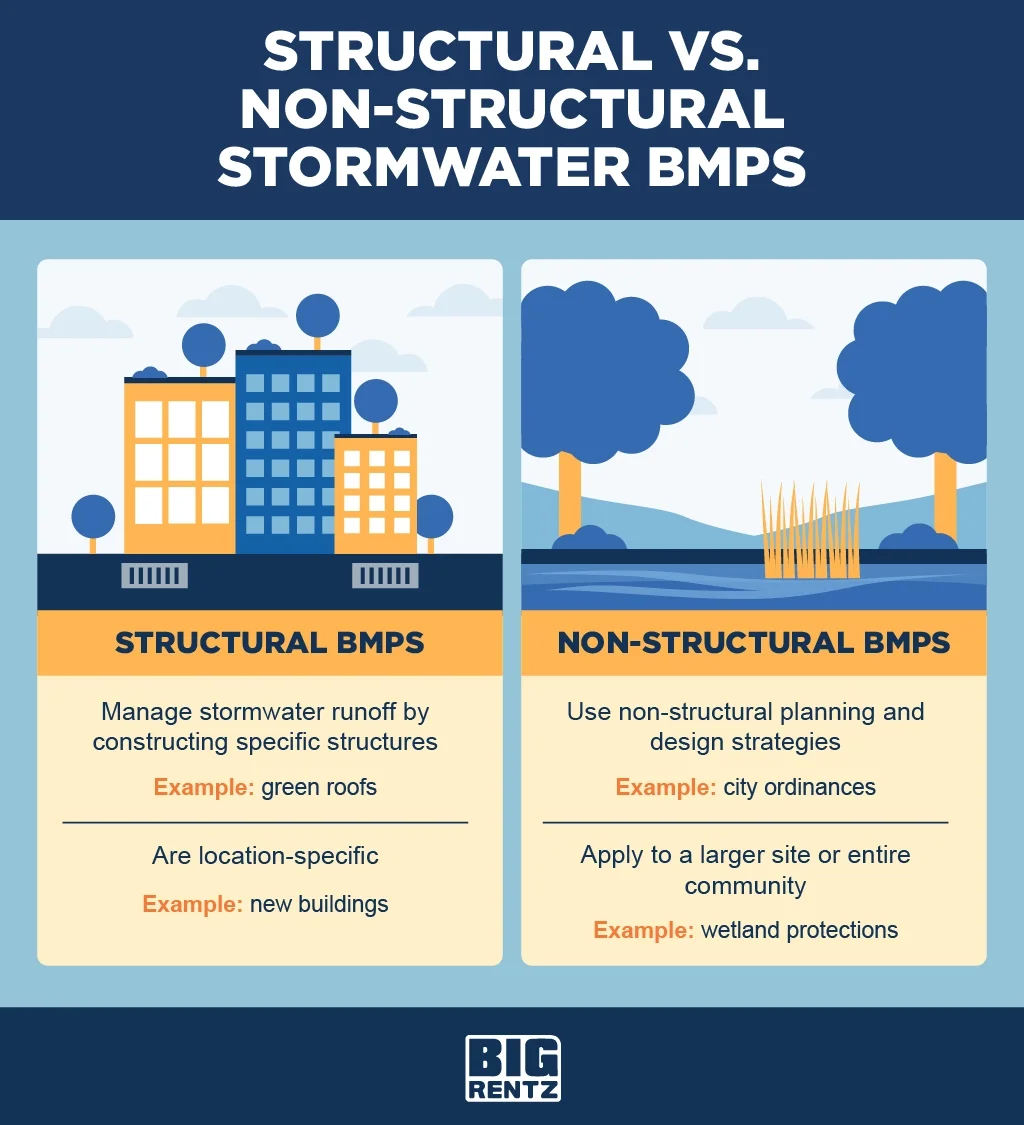

Image Credit: BigRentz.com

Failing sediment erosion control at construction site

Land cover change, in addition to improper agricultural practices, as well as an increase in impervious cover within urbanizing watersheds accelerates stream bank erosion, resulting in greater sediment and nutrient loads within the stream corridor, and can reduce groundwater infiltration, which is vital for water supply. This accelerated erosion from stormwater runoff is a result of increased volumes and velocities of water to our receiving streams from these changes in land cover. In urbanizing watersheds, downcutting or channel incision is a common within stream channels as a result of high-volume scouring flows and lateral constraints to channel migration. A 2009 study in an urbanizing Pennsylvania tributary found that stream bank erosion contributed an estimated 43% of the suspended sediment load.

Image by: IWLA Salt Watch Program

Remember all that salt sprayed on the roads during winter? As it rains, the stormwater washes the salt right into our local streams, watersheds, and ultimately, the Chesapeake Bay. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), stormwater pollution is responsible for about 10 percent of nitrogen, 31 percent of phosphorous and 19 percent of sediment in the Chesapeake Bay.

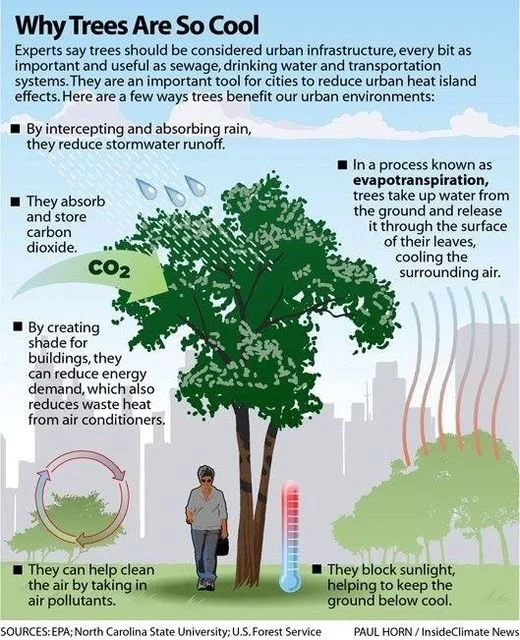

So how do we slow it down and help protect our streams? Green infrastructure is one potential option, which is a low impact Best Management Practice (BMP) that protects, restores, and mimics the natural water cycle using natural ways to control stormwater pollution. Green infrastructure is effective, economical, and enhances community safety and quality of life. At the local level, green infrastructure practices include rain gardens, permeable pavements, bioswales, urban tree canopy, green roofs, infiltration planters, trees and tree boxes, and rainwater harvesting systems. On a larger scale, the preservation and restoration of natural landscapes (such as forests, floodplains and wetlands) are critical components of green infrastructure.

Image Credit: Paul Horn Inside Climate News

How can we keep it clean or reduce pollutant loads from stormwater? In addition to the green infrastructure BMPs listed previously, additional filtering type of BMP practices to control water pollution can be installed that include, bioretention facilities, submerged gravel wetlands, and surface sand filters, as well as stormwater wet ponds, or detention basins, which are artificial ponds that collect and filter stormwater prior to it entering the stream. As stormwater is funneled into a storm drain, or inlet from streets, roofs, sidewalks, and other impervious surfaces into a stormwater BMP, if it is a filtering system like a bioretention or surface sand filter, the stormwater filters through a layer of sand, soil, and gravel, shedding nitrogen, phosphorous, and other pollutants before entering the stream channel through an underdrain pipe. If it is a wet pond or detention basin, pollutants will settle out within the pool of the wet facility as the pond discharges through the dewatering pipe. Filtering systems have a much higher pollutant removal capacity than wet ponds or detention basins. Other popular BMPs include upland tree planting and riparian buffers. Tree plantings not only filter stormwater and remove unhealthy pollutants, but they also provide habitat. Riparian buffers, which are vegetated areas along the stream bank, provide shade and regulate stream temperature, while also protecting the stream from adjacent land use, aiding in preventing erosion and sedimentation.

Image Credit: BigRentz.com

Despite decades of stormwater BMP implementation across Maryland, the continued degradation of urban streams remains a concern. The Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE), is currently in the process of advancing stormwater resiliency across Maryland and in September, 2024, released proposed changes to the States stormwater management regulations and the Maryland stormwater design manual.

Have questions or comments about this blog post? Email us!